Computing the Cyclic Decomposition and Order of Elements from Symmetric Groups

Math Background and Introduction

I am currently taking an introductory class in abstract algebra, and we have been learning about different types of groups. One of these groups is called the Symmetric Group. The symmetric group defined over any set , \(\Omega\), is denoted as \(S_{\Omega}\). This group is comprised of all of the bijections, \(\sigma : \Omega \rightarrow \Omega\). of the set onto itself, and its group operation is defined as the composition of these bijections. Since we will be looking at finite symmetric groups, we can denote the symmetric group over a finite set of \(n\) symbols as \(S_{n}\).

An example of an element in \(S_{10}\) could be the permutation (map) \(\sigma\) that rearranges [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] to be [3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 7, 9, 2, 1, 5].

(i.e. \(\sigma([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]) = [3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 7, 9, 2, 1, 5]\))

Now that we know how the elements of \(S_{n}\) act on the underlying set, what are their cyclic decompositions and orders? The order of an element in a group refers to the smallest positive integer, \(m\) such that \(\sigma^{m} = \sigma \circ \sigma \circ ... \circ \sigma = \textbf{id}\) where id is that group’s identity element. The cyclic decomposition of one of these group elements refers to the “cycles” formed when repeatedly applying the same permutation on the underlying set. In other words, the cyclic decomposition refers to the “path” that each individual set element takes under a repeated permutation to get mapped back to itself.

Viewing the permutation as a mapping of individual elements instead of a rearrangement of the entire set can aid in understanding how cyclic decompositions and repeated permutations work. Using the \(\sigma\) that we defined above, we can write out the following mapping:

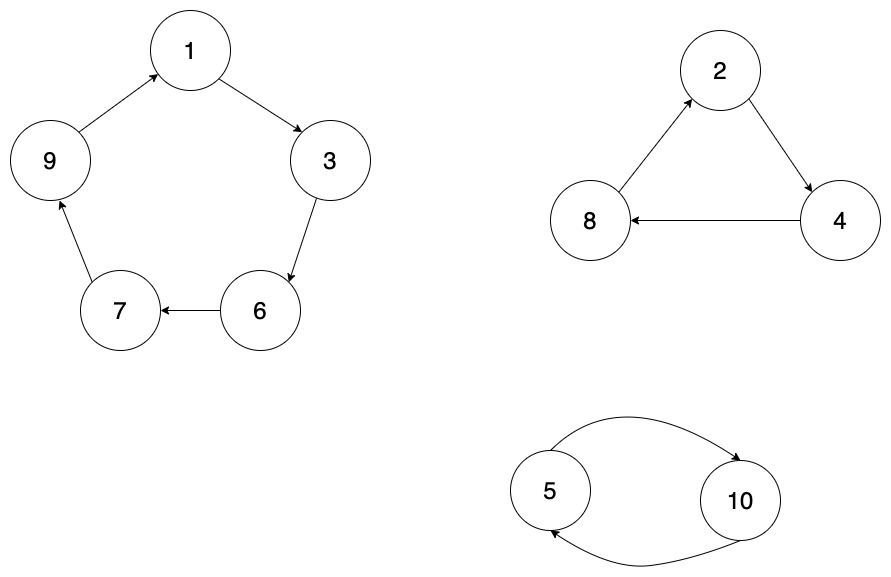

\[1 \mapsto 3\] \[2 \mapsto 4\] \[3 \mapsto 6\] \[4 \mapsto 8\] \[5 \mapsto 10\] \[6 \mapsto 7\] \[7 \mapsto 9\] \[8 \mapsto 2\] \[9 \mapsto 1\] \[10 \mapsto 5\]If we repeat this individual mapping repeatedly, we will eventually encounter elements that map back to their original positions. While sitting in class, it became apparent that this process could be automated using a directed graph and a depth-first search algorithm. The nodes of the graph would represent the set elements and the edges would represent their mapping under \(\sigma\). When the graph is drawn, the cyclic decompositions become obvious. The directed graph representing our \(\sigma\) on the set of 10 symbols is the following:

Now that we can see the cycles in the form of a directed graph, let’s take a look at the code that would allow us to generalize the process of finding the cyclic decomposition adn order of any permutaion.

Code

from math import gcd

Firstly, we can use a dictionary to stand in as our \(\sigma\) as dictionaries have keys that map to values. Since our \(\sigma\) is bijective, a dictionary with unique (key, value) pairs is precisely what we need.

sigma = {1: 3, 2: 4, 3: 6, 4: 8, 5: 10, 6: 7, 7: 9, 8: 2, 9: 1, 10: 5}

dict_keys([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

dict_values([3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 7, 9, 2, 1, 5])

Now, we use the following algorithm to find the cyclic decomposition of \(\sigma\):

1: Instantiate an array, cycles to store cycles and a set, already_seen to store elements that have been encountered

2: Iterate over the values of the underlying set

-

IF the current value is not in

already_seen, use DFS to repeat \(\sigma\) until the value is repeated.- Append every element seen to

cyclesand updatealready_seento include these elements.

- Append every element seen to

3: Return cycles

In Python code, this algorithm would be

def find_cyles(sigma):

"""Find cycles of a map using a depth first search"""

cycles = []

already_seen = set()

for element in sigma.keys():

if element not in already_seen:

cycles.append(dfs(sigma, element, set(), []))

already_seen.update(cycles[-1])

return cycles

def dfs(sigma, element, memo, cycle):

"""DFS Helper Function"""

if element in memo:

return

memo.add(element)

dfs(sigma, sigma[element], memo, cycle)

return list(memo)

DFS (depth-first search) is a graph traversal algorithm that starts at a “root” node and explores as far down that each of root’s branches as possible before backtracking and moving onto the next branch. Below is a gif that shows how DFS traverses a graph (Source)

To find the order, we can use a theorem which states that the order, \(m\),of a permutation is the least common multiple of the lengths of each cycle. By using this theorem, we can use the result from our DFS and avoid having to use the brute-force solution where we would compose \(\sigma\) with itself until we map back to the original ordering of elements.

def find_order(cycle_list):

"""Compute LCM of Cycle Lengths"""

cycle_lengths = [len(x) for x in cycle_list]

lcm = cycle_lengths[0]

for length in cycle_lengths[1:]:

lcm = lcm*length//gcd(lcm, length)

return lcm

Now that we have these Python functions, we can use them in conjunction to find the order and cyclic decomposition for any map that belongs to a finite symmetric group! (Note: the notation for the cyclic decomposition (1 3 6 7 9) (8 2 4) (10 5) refers to the disjoint cycles that are produced. 1 maps to 3, 3 maps to 6, and so on.)

cycles = find_cyles(sigma)

cycles_string = ''

for cycle in cycles:

cycles_string += str(tuple(cycle)) + ' '

print('The Cyclic Decomposition of Sigma is {}'.format(cycles_string))

print('\nSigma has order {}'.format(find_order(cycles)))

The Cyclic Decomposition of Sigma is (1, 3, 6, 7, 9) (8, 2, 4) (10, 5)

Sigma has order 30

Conclusion

Graphs are an extremely versitile tool that allow us to represent both abstract mathematical objects and physical networks as data in memory. By using DFS, we can traverse these graphs that represent the permutations of a set to learn more about their underlying structures… and we can automate some problems from our abstract algebra homework.