Reproducing 'Does data interpolation contradict statistical optimality?'

Introduction

During one of my biweekly research meetings, my group reviewed Does data interpolation contradict statistical optimality? by Mikhail Belkin, Alexander Rakhlin, and Alexandre B, Tsybakov

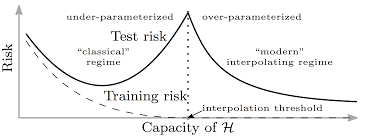

The aim of this paper was to show that interpolating training data can still lead to optimal results in nonparametric regression and prediction with square loss. Since the double descent phenomenon exhibits itself when the model capacity surpasses the “interpolation threshold”, I thought that reproducing the results from this paper would help me understand how a model interpolates data.

[1]

)

)

Math and Code

import numpy as np

import os

import numpy.linalg as lin

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import scipy.stats as stats

This paper takes a look at interpolation using the Nadaraya-Watson Estimator.

Let \((X, Y)\) be a random pair on \(\mathbb{R}^{d} \times \mathbb{R}\) with distribution \(P_{XY}\), and let \(\mathbb{E}[Y \vert X = x]\) be the regression function.

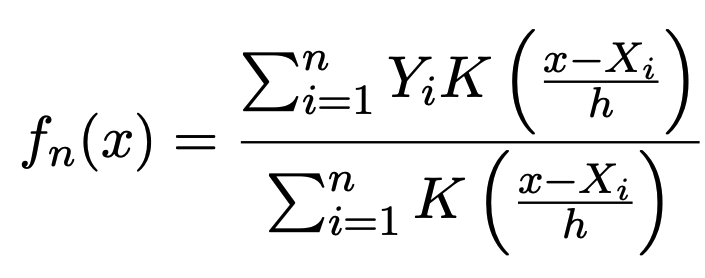

Given a sample \((X_{1}, Y_{1}),...,(X_{n}, Y_{n})\) drawn independently from \(P_{XY}\), we can approximate $f(x)$ using the Nadaraya-Watson Estimator where \(K: \mathbb{R}^{d} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is a kernel function and \(h > 0\) is a bandwidth

def nadaraya_watson_estimator(x, X, Y, h, K=stats.norm.pdf):

cols=[]

for i in range(len(X)):

cols.append(np.array(K((x - X[i])/h)))

Kx = np.column_stack(tuple(cols))

row_sums = np.sum(Kx, axis=1)

W = Kx / row_sums[:, None]

result = np.matmul(W,Y)

result.shape = (result.shape[0], 1)

return result

Note: Since we are dealing with singular kernels that approach infinity when their argument tends to zero, we will have to use a modified version

def singular_nadaraya_watson_estimator(x, X, Y, h, K=stats.norm.pdf, a=1):

cols = []

for i in range(len(X)):

condition = False

for boolean in [k==0 for k in x - X[i]]:

if boolean:

condition = True

cols.append(np.array([Y[i]] * len(x)))

break

if condition == False:

cols.append(np.array(K((x - X[i])/h, a)))

Kx = np.column_stack(tuple(cols))

row_sums = np.sum(Kx, axis=1)

W = Kx / row_sums[:, None]

result = np.matmul(W,Y)

result.shape = (result.shape[0], 1)

return result

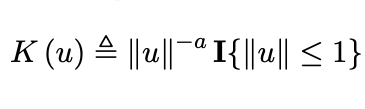

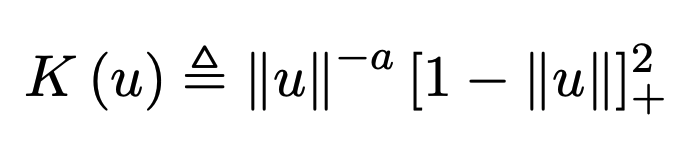

The two singular kernels we will be focusing on are:

def sing_kernel_1(x,a):

return 1/(abs(x))**a

and

def sing_kernel_2(x, a):

return (1/(abs(x))**a)*(1-abs(x))**2

The data generating functions we will look at are

def actual_regression_1(x):

return 5*np.sin(x)

and

def binary_classification(x):

outs = np.array([])

for element in x:

if abs(element) > .4:

outs = np.append(outs, [1])

else:

outs = np.append(outs, [0])

return outs

Some notes:

- Because of input size mismatches, I used

abs()instead oflinalg.norm()since I pass in the elements as arrays, but they are really (x, y) which are both just 1 dimensional real numbers - The indicator function on

sing_kernel_1gave me errors when I tried implementing it, so i removed it. The kernel’s singularity as the argument goes to infinity is still present. - The data from the sinusoidal function (p.4 of the paper) does not seem to be randomly sampled, so I did not randomly sample it either

Results

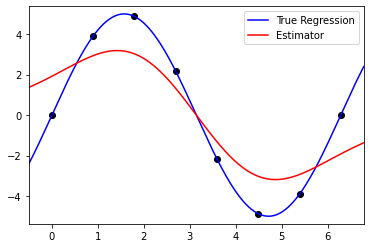

Sine curve with singular_kernel_1:

The estimator fits the curve fairly well for values of a > .8. For some reason, the bandwidth, h, doesn’t do anything to this specific example. Because the best value of h in the paper was .4, I chose to keep h constant.

Sine curve with standard Gaussian kernel:

There are no animations for different parameters because the only tunable parameter is the bandwidth, h, which was held constant at .4

Code (from notebook)

#np.random.seed(100)

n = 8

#epsilon = np.random.normal(loc = 0, scale = 2, size = n)

X = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, n)

#np.random.normal(loc = 0, scale = 3, size=n)

Y = actual_distribution_1(X)

x_axis = np.linspace(-1, 7, 100000)

# Singular Kernel

h=.4

a=1.5

plt.scatter(X, Y, color='k')

plt.plot(x_axis, actual_distribution_1(x_axis), 'b-')

plt.plot(x_axis, singular_nadaraya_watson_estimator(x_axis, X, Y, h, K=sing_kernel_1,a=a), 'r-')

plt.xlim(min(X) - .5, max(X) + .5)

plt.ylim(min(Y) - .5, max(Y) + .5)

plt.legend(['True Regression', 'Estimator'])

plt.show()

# Non-singular Kernel

h=n**(-1/(2*0 + len(x_axis)))

plt.scatter(X, Y, color='k')

plt.plot(x_axis, actual_distribution_1(x_axis), 'b-')

plt.plot(x_axis, nadaraya_watson_estimator(x_axis, X, Y, h), 'r-')

plt.xlim(min(X) - .5, max(X) + .5)

plt.ylim(min(Y) - .5, max(Y) + .5)

plt.legend(['True Regression', 'Estimator'])

plt.show()

Binary Data with singular_kernel_2:

In this animation, I sweep through several values for h with a constant. Then I hold h constant and sweep through several values of a

Binary data with standard Gaussian kernel

The only tunable parameter here is h

Code (from notebook)

#np.random.seed(100)

n = 8

#epsilon = np.random.normal(loc = 0, scale = 2, size = n)

X = np.random.choice(np.linspace(-1, 1, 20), n)

Y = binary_distribution(X)

x_axis = np.linspace(-1, 1, 500)

h=n**(-1/(2*0 + len(x_axis)))

a=1

plt.scatter(X, Y, color='k')

plt.plot(x_axis, np.array([.5] * len(x_axis)), 'b--')

plt.plot(x_axis, singular_nadaraya_watson_estimator(x_axis, X, Y, h, K=sing_kernel_2, a=a), 'r-')

plt.xlim(min(X) -.1, max(X) + .1)

plt.ylim(min(Y) - .1, max(Y) + .1)

plt.title('a = {:.2f}; h = {:.2f}'.format(a, h), fontsize=12)

plt.legend(['Boundary', 'Estimator'])

plt.show()

h =.4

plt.scatter(X, Y, color='k')

plt.plot(x_axis, np.array([.5] * len(x_axis)), 'b--')

plt.plot(x_axis, nadaraya_watson_estimator(x_axis, X, Y, h), 'r-')

plt.xlim(min(X) - .1, max(X) + .1)

plt.ylim(min(Y) - .1, max(Y) + .1)

plt.title('h = {:.2f}'.format(h))

plt.legend(['Boundary', 'Estimator'])

plt.show()

Conclusion

After reproducing these results, I emailed Mikhail Belkin to get his thoughts on the connection between this paper and a previous paper he wrote on the double descent phenomenon. His reply was very similar to what my group thought the connection may be: interpolation is consistent with the current practice of deep learning. The most important thing to realize is that there is still not a proven, complete connection between modern machine learning methods and the model shown in this post.

References:

- Does data interpolation contradict statistical optimality? - https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.09471

- [1] - https://www.cs.ubc.ca/labs/lci/mlrg/slides/dl_generalization.pdf